Help Us, Civic Man (and Woman)

I want to tell you the story of my Grandpa Sheffer, who rose from an inauspicious beginning to become someone our country desperately needs today: "Civic Man."

Civic Men and Women are the amateur politicians and volunteers who set our property tax rates, fix and maintain our roads and bridges, put out fires, run our schools, pick up our trash, plow our streets, and try to grow businesses and jobs in our communities. They do it for little or no pay in and around their "day jobs."

They do more to affect your life than professional politicians.

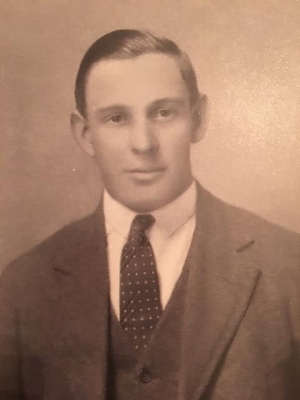

Elmer Richmond Sheffer was one of them. He was born at home on South Sixth Street in Hudson, N.Y., in 1906. He weighed 1 1/2 pounds at birth. It was a difficult delivery for his mother and afterward, his Aunt Minerva wrapped Elmer in a soft blanket, put him in a cigar box and placed it near the wood-fired oven in what seemed like a hopeless attempt to keep him alive. As he would many times in his life, Elmer rallied and surprised everyone by growing into a tall and strong young man. He overcame the challenges of a broken home and abandonment by his mother, spent his entire life in his birth home, and was raised by his grandparents, Phelitus and Lydia Richmond.

Elmer graduated from Hudson High in 1924 and landed a job as a physical chemist at the now abandoned Lone Star Cement plant in Hudson. The job lasted 44 years, giving him a reliable but modest living and the stability to become a Civic Man.

Elmer waded into Hudson politics shortly after becoming eligible to vote at age 21. He registered as a Republican to be a contrarian in a Democratic family. He became an alderman and ran unsuccessfully for mayor in 1951. He stuck with politics and in 1965, mayoral candidate Sam Wheeler asked Elmer to be on his "ticket" and run for president of the common council. They won that year and again in 1967.

Elmer's high school graduation photo.

Two years later, it was Elmer's turn. Because he was retired he ran under the slogan, "Hudson's First Full-Time Mayor," to demonstrate his commitment to Hudson, a down-on-its-luck city of 15,000. He won a two-year term and was re-elected in 1971.

He was a natural politician -- smart, gregarious, a great negotiator and counselor. Someone once joked at a dinner I attended that Mayor Sheffer could speak at the drop of a spoon. Elmer proved him right. Patrons at the Elks Lodge bar would yell "Mayor!" when he walked in, a toothpick or cigar in his mouth. He responded with a tip of the cap or an exaggerated politician's wave of the hand.

He loved the job and I loved being the grandson of the mayor. Because I was, my friends thought my family was rich (we weren't) and that we got special privileges (we didn't). Thanks to Looney Tunes cartoons on TV, they also liked to make fun of his name. Come to think of it, he probably was the last person named "Elmer" elected to public office in the U.S. (his political opponents once ran an ad criticizing his policies as "Elmer's Goo.").

In 1973, the local political winds shifted and his party abandoned him. Elmer was disappointed but it did not stop Civic Man.

He threw himself into other community passions. Elmer was a firefighter with the J.W. Edmonds Hose Co. No. 1 and served as its treasurer for more than 40 years. When he could no longer fight fires, he was active in the fire police, directing traffic and people at fire and emergency scenes. He helped form the Hudson Elks Little League and spent many hours grooming the field, managing teams and umpiring. A few years ago, just before his son and my father, Red Sheffer, passed away, the Hudson Elks posthumously named the Little League field after Elmer. Sadly, the sign bearing his name has been removed and field renamed. Apparently, gratitude for the work of Civic Men and Women doesn't last forever.

In his twilight, he would sit outside his home, smoke a cigar, pet his dog Ringo and talk to everyone who walked by. His daughter, Elizabeth "Bitsy" Sheffer-Winig, remembers that he never turned away any of the aspiring young politicians who came to his house for advice. He loved his children and grandchildren fervently.

By the time I got to know him better as a teenager, he had a jowly face but retained the lanky frame of the gifted athlete who played softball for the Elks into his 50s. Diagnosed with liver cancer in 1981, he didn't give up. An experimental treatment sent the cancer into remission and gave him a few extra years. The tumor regrew but this time Elmer could not rally. The Hudson Fire Department and the Hudson Police escorted his casket to the cemetery.

Holding Court: Grandpa and Ringo

I was thinking about my grandfather recently and it struck me that it is harder today to be a Civic Man or Woman. Reliable jobs, which give people the ability to volunteer and serve others, are scarce in small towns and rural areas. Plus, the dysfunction of Washington, D.C., has created a falsely dark view of our country. Our problems seem so daunting that there is little Civic Man can do. Perhaps this causes us to look to the powerful for answers rather than creating them ourselves.

I tell you the story of my grandfather not to lionize him but as a reminder that great acts are possible close to home (my grandfather spent 99% of his life on one square mile of earth). Serving on a school board or running a youth baseball league is as powerful collectively as any presidential order. Former President Obama said in his farewell speech that change only happens when "ordinary people get involved, get engaged and come together to demand it." Grandpa Sheffer was that ordinary citizen -- a Civic Man. We need more of them.